In this time of modified operations, businesses and organizations of all types are faced with enormous challenges in labeling anything as “business as usual.” For the performing arts community, this has meant limiting the number of patrons, changing how to reach them, and of course navigating stressful financial realities. Re-opening, in whatever format, has also required organizations to provide for the safety of patrons. This has meant installing plexiglass barriers in some cases, providing face masks, and stocking up on hand sanitizer – oh the hand sanitizer.

Did you know that hand sanitizer may pose a fire risk to your staff, performers, or patrons if not stored and used properly? Has your organization considered the risk involved? Not surprisingly, a quite reasonable answer to this is most likely, “Of course not, we had no idea!”

Fire safety and protection is, for the most part, guided by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). Since 1896, this self-funded nonprofit organization has devoted itself to eliminating death, injury, property and economic loss due to fire, electrical and related hazards[1]. Through the collaboration of various industry professionals, codes and standards are provided for fire departments worldwide to use in the delivery of fire safety and emergency response.

NFPA 101: Life Safety Code is the foundational fire safety guidance; the purpose of this Code is to “provide minimum requirements, with due regard to function, for the design, operation, and maintenance of buildings and structures for safety to life from fire. Its provisions will also aid life safety in similar emergencies[2].” Although first included in 2006 for health care facilities, the 2018 update made alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) provisions applicable to all types of buildings and facilities.

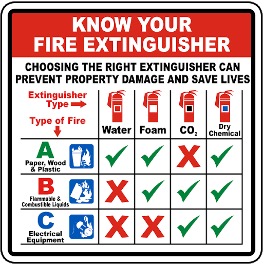

The risks of ABHR stem from flammability and vapor hazards. They are classified as Class I Flammable Liquid substances, which means they have a flash point of less than 100 degrees Fahrenheit. In the event that hand sanitizer combusts, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide can form. You can learn more about your specific product by reading the container label or by referring to the Safety Data Sheet (SDS) for that item. These risks can be minimized if spills are cleaned immediately, if proper storage is used, and if fires are extinguished rapidly. The worst case only need happen if we do not take any precautions.

To find your specific SDS, try this free SDS Search Tool. To learn more, read the OSHA Brief for Safety Data Sheets.

Storage of these materials are required by NFPA 101 to be in an approved fire cabinet or storage device. Each cabinet is restricted to hold a cumulative amount of 10 gallons of ABHR. This includes any combination of liquid or aerosol containers. As you consider the quantities you are purchasing, keep in mind that you may only be able to appropriately store a certain quantity because of the storage requirements. When budgeting for hand sanitizer, you should also include

an approved flammable liquids storage cabinet.

Use of hand sanitizers is also addressed in the Life Safety Code. This is perhaps the most important section because of the potential for misuse, which may lead to an unfortunate event. To start, individual dispensers should be limited to .53 gallons (2 L) when used in rooms separated by hallways. Dispensers that are located in hallways or open areas are limited to .32 gallons (1.2 L). Aerosol dispensers should contain no more than 18 oz. This means that the gallon size jug with a pump may not be on a table in your lobby area, it exceeds the maximum capacity.

Use of hand sanitizers is also addressed in the Life Safety Code. This is perhaps the most important section because of the potential for misuse, which may lead to an unfortunate event. To start, individual dispensers should be limited to .53 gallons (2 L) when used in rooms separated by hallways. Dispensers that are located in hallways or open areas are limited to .32 gallons (1.2 L). Aerosol dispensers should contain no more than 18 oz. This means that the gallon size jug with a pump may not be on a table in your lobby area, it exceeds the maximum capacity.

We should also pay attention to where the dispensers are installed. The NFPA code says they need to be separated from each other by 4 feet of horizontal spacing. Additionally, dispensers cannot be installed in close proximity to any sort of ignition

source. Installing in areas with carpeted floors is only allowed if that area is covered by fire sprinklers; this is meant to minimize the hazard, by reducing the amounts of ABHR in a small area, should a fire occur.

If a fire should happen, of course the priority becomes following emergency plans already established for your organization. In the case that the fire is recognized early enough, and it is small enough, a fire extinguisher should be used. A small fire is considered approximately the size of a small trash can. Extinguishers with the A, B, C rating are most commonly used and are appropriate for this scenario. For more on how to select and use fire extinguishers, watch this OSHA Training Tutorial.

If a fire should happen, of course the priority becomes following emergency plans already established for your organization. In the case that the fire is recognized early enough, and it is small enough, a fire extinguisher should be used. A small fire is considered approximately the size of a small trash can. Extinguishers with the A, B, C rating are most commonly used and are appropriate for this scenario. For more on how to select and use fire extinguishers, watch this OSHA Training Tutorial.

Performing arts organizations have been doing their best to determine the path forward and are doing an amazing job at it. However, there are some things that they just do not have in-house knowledge to address. According to a 2016 white paper published by LYRASIS, risk analysis and emergency preparedness are not widespread skill sets among performing arts organizations.

The Paper, titled “Acting Now to Enhance Performing Arts Emergency Preparedness”, describes a survey conducted among member organizations of the National Performance Network (NPN).

“Results indicated to project partners that a majority of the performing arts organizations participating did not have disaster plans, and even fewer have continuity of operations plans (CoOP). Only 30% of the responding partners and none of the responding service organizations had disaster plans; 27% of the NPN partners and one of the service organizations had CoOPs. This type of planning is not an institutional priority, according to the survey results, and organizations do not have the time or expertise to develop such plans.[3]”

Remembering that the NFPA’s goal is to enhance our ability as organizational caretakers to provide for safety to life from fire, this is an essential element in providing comprehensive protection for routine emergencies and true crisis situations. Application of another code, NFPA 909 for Cultural Resource Properties, is a tool that provides a template for a complete protection plan that merges fire safety and typical emergency management strategies. Having someone who is well versed in this area can be a great addition to your planning team.

Your local fire department can be an invaluable resource for further understanding of the NFPA requirements and overall fire safety. However, for developing written plans or understanding fire safety as part of facility improvement plans, it is useful to consult with a knowledgable consultant. I encourage every organization to explore working with the Performing Arts Readiness Project, and be sure to include fire safety in your planning. Their website is full of information, including the Fire Safety and Preparedness for Performing Arts Organizations webinar.

###

Chris Soliz ([email protected])is a PAR project consultant. After a successful 28-year career as a firefighter and emergency management professional, he now works with non-profits for fire safety and preparedness. He has worked with government, private, and non-profit organizations to develop plans, command large-scale emergencies, manage special events, and coordinate resource management. Chris holds a Master’s Degree in Emergency Services Management and is credentialed as an Incident Commander for North Carolina’s Incident Management Team. He is currently an Instructor for Western Carolina University’s Emergency Management Degree Program and also serves on the Board of Directors for the Family Crisis Council; a non-profit organization whose mission is to empower victims of sexual assault and domestic violence to take back their lives.

[1] NFPA Overview, https://www.nfpa.org/overview, 2021

[2] Life Safety Code, National Fire Protection Association, 2018

[3] Acting Now to Enhance Performing Arts Emergency Preparedness, Thomas F. R. Clareson and Sandra Nyberg, LYRASIS, 2016